The nature of death is not easy to define. Our concept of it has changed over time. There has always been and will continue to be a fine line between life and death.

Over and above scientific and legal issues, which are of course hugely important, death still holds many unknowns for human beings, who live always in its shadow. No-one who has died can tell us what it feels like.

What we do have is accounts of near-death experiences from people who can describe those moments when they felt that the way back from the edge was receding endlessly. But ultimately no-one who has come back at the last minute can claim really to have known death. By its very nature, death is door that only opens one way.

As we get older the likelihood of experiencing those moments more or less close to the end comes nearer. There is no need to suffer a tragic accident or a near fatal illness to feel the gloom of depression, heartbreak, war, prison or persecution, all of which have a scent of death about them.

Any effort to collect statements from people who one day thought they were going to die reveals that there are many more of them than might be thought: the bather pulled from the waves, the heart-attack victim shocked back by a defibrillator, etc. Such episodes appear frequently in films. A case in point is the unforgettable scene in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction in which John Travolta saves Uma Thurman from dying following a cocaine overdose by injecting a massive shot of adrenalin directly into her heart.

When the unlikely topic of death crops up in conversation, a recurrent question is how one would prefer to die if given the unlikely privilege of choosing. There are many answers: some say peacefully in bed, painlessly unaware and surrounded by their loved ones; others say with their boots on, working and fighting for their favourite cause until they lose the final battle, but with the hope that someone else will pick up where they leave off.

The topic has taken on a higher profile with increasing calls in society for the right to die with dignity, with assistance if necessary to put a fitting end to the unique, unrepeatable experience that we call life. But legislation is slow to change in each country, because all societies act with caution in this matter, which is extremely delicate and steeped in taboos.

What the future deceased can choose as part of their last will and testament is what is done with their remains. But with the exception of a few great personages, even that choice may not be forever, because soon the world will run out of places to put the dead.

The Internet now provides an unlikely new source of hope that one will never be forgotten. But will today’s software and data carriers really remain active and operational, enabling our pictures and records to be retrieved in thousands of years’ time just as they can today?

In spite of all the wide variety of ways of handling death and the arrangements that come after it, human beings are almost unanimous in their desire to put it off for as long as possible. And that is only natural: life is the only world that we know, so why be in a hurry to leave it?

In tackling this last, irreversible challenge, religious believers have the added backing of their faith in a life beyond this world. They see the feared end of life as a mere stepping-stone to a new experience. Those without religious faith may simply believe, like Stephen Hawking, that, “when one’s expectations are reduced to zero, one really appreciates everything one does have”, and die in the singularity in which the desire to survive grows and intensifies endlessly as time runs out.

What is certain is that although the concept of death may have changed over time, life has always been and will always be ephemeral. Even the longest life lasts only for a short time and then is gone.

Another recurring question is whether we come to understand things better as the end approaches.

In his classic song Suzanne, Leonard Cohen puts this question into the mind of Jesus and sketches out an answer in the line “And when he knew for certain only drowning men could see him…”.

Suzanne’s young lover was irremediably drowning in the magnetism of her irresistible attractiveness, knowing that he could trust her, “For [he’d] touched her perfect body with [his] mind”.

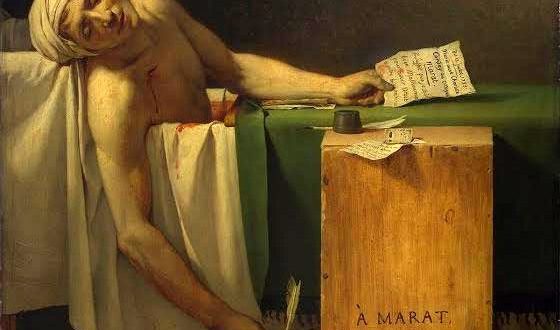

Trust is one of life’s most sought-after treasures, though the search is often an unconscious one. Death is always cruel, but it may be doubly so when it takes a loved one. In the words of Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes[1] the most painful death “is not our own but that of those we love”.

Leonard Cohen’s words, which are now part of his artistic legacy, take on even more importance in these days of firm but groundless convictions, when power whips away truth.

But what if it is true that only the drowning can see? What would they say to us if they could avoid that last mouthful of water that floods into their lungs and ends their lives?

In today’s tangled world packed with contradictory, mutually exclusive certainties, there is a temptation to listen only to the voices of those who lost their lives howling what they were seeing as they drowned. What if, as they struggle for breath, they are the only ones capable of providing us with truly transcendental information, while the rest of us live on blindly?

That young man to whom Suzanne gave tea and oranges that came all the way from China was one of those who could see as he drowned. But there must be many more around.

If all those drowning people one day simultaneously told us what they were seeing, we might have more of a clue as to what the future has in store for us. But that will never happen and we will continue to wander aimlessly, guided by those who see only a mirage of certainty. That is always how it will be and, as Cohen said, only drowning men can see.

The universe designed itself perfectly in such a way that those who see cannot tell, so everyone must continue their own search unceasingly until the end. Perhaps they see us as lost in our earthly maze, unable to whisper the clues that they have learnt, to no avail, after being sucked into the last whirlpool.

But all human beings need to escape, even if only in their imagination, from cold reality. Perhaps that is why in their dreams everyone hears their forbears, those who are no longer with them, those whom cruel death has taken from them, as Fuentes put it, whispering the secret of that last flash of light in their ears.

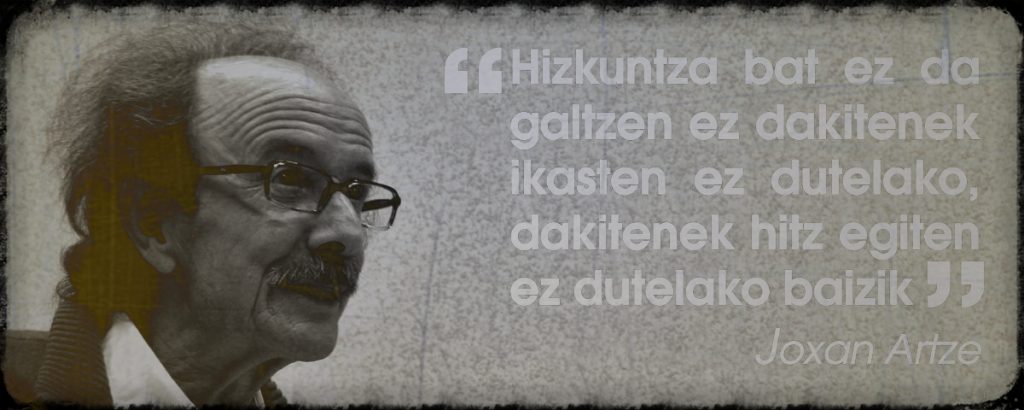

What goes for individuals applies equally to people and cultures, which can also die. Large ones may drift on unawares, leaving their future in the hands of fate. Small ones, however, run the risk of realising the truth only when the waves engulf them. Perhaps that is why our ancestors left us messages intended to wake us up when laziness turns to dozing and dozing turns to a sleep from which there is no coming back. Basque poet and musician Joxean Artze said “a language is not lost because it is not learnt by those who do not know it, but because it is not spoken by those who do[2]”.

But even this may not be the right epitaph for what seems destined to be a world without frontiers, in which billions of human beings wander the planet living their lives more or less with dignity, generation after generation, to forge perhaps at last a single, common culture filled with nuances and blurred edge.“No es la que nos mata a nosotros sino a los que amamos”.

Enrique Zuazua is mathematician, FAU-Humboldt Erlangen, Fundación Deusto and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

The original article was published in the DEIA newspaper on November 15, 2019 and can be downloaded in PDF from this link.

1) “No es la que nos mata a nosotros sino a los que amamos”

2) “Hizkuntza bat ez da galtzen ez dakitenek ikasten ez dutelako, dakitenek hitz egiten ez dutelako baizik”

[1] English translation by Chris Pellow