We were born and raised in a world that we thought was safe. In the 1960s the Spanish Civil War was fading to a distant memory for most families. No-one said much about those tragic times that so irreversibly upset the lives of our parents and grandparents. The victory was not glorious enough, nor the defeat epic enough, to be worth telling stories about. There was tacit agreement that it was inadvisable to tell the youngest members of society about that shameful episode.

We were born just as the economy was taking off, hunger was ceasing to be a threat and the future was beginning to look brighter, though it would plainly still be fraught with difficulties and uncertainties.

We lived under a dictatorship, but most people found the minimal amount of freedom allowed acceptable. All this did not of course rule out hope for a rebellion that would give us back our rights and our liberty.

We felt safe. As kids we could roam the local streets with no fear of being kidnapped or abused.

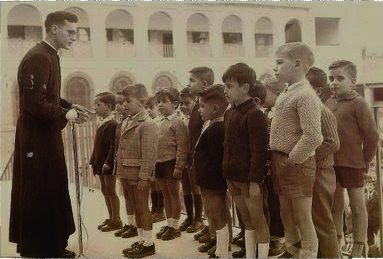

School was often harsh in excess, and corporal punishment was a very real possibility. But in those days it was seen as acceptable, and the toughest teachers could point to popular sayings that supported their attitudes: “spare the rod and spoil the child”, “you have to be cruel to be kind”, etc. For most of us, corporal punishment at school entailed just the odd unpleasant incident, but in some cases pupils were picked on systematically and left with deep, long-lasting traumas. That too was considered as normal. Some pupils were very good, many more were passably good and a few went through hell at school. The fate of each and the roles in which they were cast were seen as inevitable, as if any statistics involving large numbers must include a few individuals who suffered.

Every family had its dramas. But dirty linen was not washed in public.

The newspapers kept things simple and did not poke their noses into delicate social issues. There was censorship, and most of the media that we use today had not yet been invented.

Against this background of accepting injustice in a society that was undergoing invisible but rapid change, we still felt safe overall. Routine helped make us feel that way.

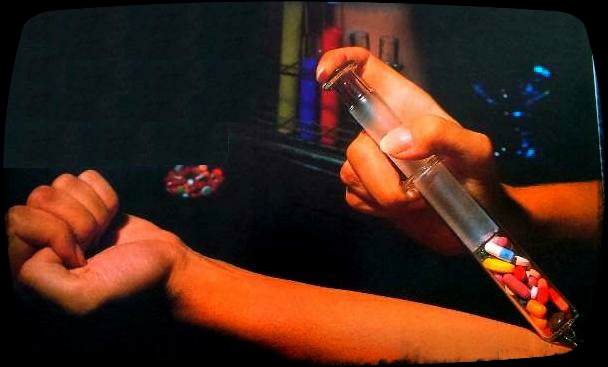

Everything seemed to occur in moderation. People drank and smoked, but apparently not in excess. Drugs did not officially even exist, though they were frequently sold over the counter at the chemist’s. But for most people life was austere and remedies were almost all home-made, such as camomile tea made from flowers collected in the fields around us.

People did not travel far, and road and air accident statistics were hardly even compiled.

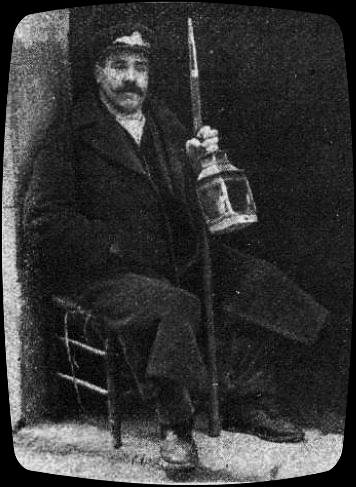

It was a society in which sexuality was deeply repressed and there were apparently no rapes. There were no streets that could be classed as no-go areas by day or by night, but neighbourhood night watchmen kept an eye out after dark just in case.

Little by little, society began to come to the boil. Political protests began, sometimes leading to confrontations with the police. Some took up arms, and this was seen as a justified revival of a war that had cut short so many plans for justice and freedom.

When the bombings and shootings began they seemed to be aimed at a select few. Most of us were lucky enough not to be implicated, not to have any pro-ETA activists in our families and not to be targets. We still lived in a world that seemed safe.

Even the transition to democracy went off in a relatively peaceful, celebratory fashion.

After the transition to democracy, drugs came flooding in. There were many victims, but even that was accepted with the same resignation and sense of inevitability or of them having it coming as with corporal punishment at school.

But the problems worsened. Dissatisfaction spread almost incomprehensibly in a society that was moving firmly towards the future and progress, and violence gradually worked its way into our everyday lives.

It began to be called terrorism. In the early days the kidnappers sat and played cards with the kidnapped, but before long the latter were running the risk of being cruelly killed in the name of a cause.

The shootings and bombings, at first rare events almost always directed at known proponents of repression, spread indiscriminately. But even in that inhuman escalation there seemed to be a logic that could be explained in terms of a tolerable social confrontation. We still felt as if we lived in a safe world, even as the number of people under threat increased apace with the victims of overdoses and traffic accidents.

There seemed to be a logic of reversibility in everything. And indeed there was. Little by little the guns fell silent, the drugs were reined in and road accidents were reduced through fines and penalties and via improvements in vehicles and roads.

But as the risks inherent in a hasty, complex transition for which we were not fully prepared were brought under control, new risks emerged.

Women began to run the risk of being raped in broad daylight, domestic violence increased, the victims of AIDS outnumbered those of the toxic rapeseed oil scandal of the 1980s and the old problem of violence at school due to excessively severe teachers morphed into bullying among pupils. Cyber-bullying emerged, along with role-play games more dangerous than the air guns that we played with in the fields as children or the harpoons used by divers back in the day when the sea was full of fish.

But it all felt like part of a script. Increasingly complex, sophisticated drugs gave rise to new troubles that needed to be tackled again with justice, information and education.

A society where few people had moved far from their place of birth and “immigrants” had meant people from neighbouring provinces began to receive migrants from multi-ethnic backgrounds. Our reaction to this was hardly subtle. We had been taught “when in Rome, do as the Romans do”, and on that basis we felt that integration was just a matter of time and the goodwill that we all believed that we possessed.

In neighbouring countries where immigration had begun decades earlier, we began to see that, paradoxically, things seemed to get more complicated in the second or third generation, to the point where hate and confrontations ensued.

But this too was taken on board matter-of-factly and integrated into a system that was learning: integrating foreigners was not as easy as it seemed, so more care needed to be taken, including the use of politically correct language.

Then everything changed on a global scale. At a time when the Vietnam War had become a story told in films, a new generation of modern wars emerged with sophisticated weaponry and brightly coloured missiles that we could watch live on TV.

Charlie Rose interviews Samuel P. Huntington (author of “The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking World Order”) in 1997

And suddenly the world was involved in a war of civilisations. But this too could be integrated into our way of thinking: it was the fault or the old imperialists, the usual tin-pot dictators and insatiable financial interests.

Another 20 years have passed. Our society has dressed itself up in technology to an extent that would hitherto have been unthinkable. But discordance seems to be gaining ground day by day all over the world.

If we make the effort we can also explain what is happening here and there right now. But after this brief recapitulation of recent history, if there is one thing that is clear it is that it is not clear where we are heading. Does anyone know?

The original article was published in Spanish in DEIA newspaper on December 5, 2019 and can be downloaded from this link.

[1] English translation by Chris Pellow