A few days ago the newspapers reported a story that was new here, though the same has happened in neighbouring countries in recent years so it should have come as no surprise: in the latest round of competitive examinations for public employment only a little more than half of the vacancies for upper secondary maths teachers in public education were filled. What is going on? This would have been inconceivable just a few years ago. And it is all the more striking in a country where youth unemployment is a major concern.

The first explanation that comes to mind is that today’s job market offers other, more attractive opportunities for young people who graduate in a STEM subject (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). Holders of such degrees are no longer limited to being upper secondary teachers or, with luck, university lecturers. They can now choose from an endless range of possibilities all across a society that is governed more and more by numbers. This is the age of Big Data, with vast amounts of information handled by computers.

We are living in historic times. The path that human beings took when they began to develop mathematics as a way of understanding the world was the right one. It has guided them in designing the high-tech, global society in which we live. The pace of change is accelerating and demand for mathematics is increasing in all areas. Every business, whatever its area of operation, aspires to have one or more mathematicians on its payroll to analyse data, tackle complex issues and guide it through its digital transition.

We are living in historic times. The path that human beings took when they began to develop mathematics as a way of understanding the world was the right one. It has guided them in designing the high-tech, global society in which we live. The pace of change is accelerating and demand for mathematics is increasing in all areas. Every business, whatever its area of operation, aspires to have one or more mathematicians on its payroll to analyse data, tackle complex issues and guide it through its digital transition.

But this widespread demand for maths does not in itself explain why teaching posts are being left vacant. Our society is changing, and so are the expectations of young people. They may no longer see themselves as having a lifelong career as a teacher. As society moves forward and globalises at a headlong pace the job stability that was so sought-after until recently may now be seen as monotony or stagnation. With rare exceptions, a vocation no longer suffices in itself to convince a young person to take up a profession for life.

The situation is paradoxical. Now that maths is more important than ever in the education process, we are having trouble recruiting teachers. Drafting in holders of other qualifications to fill the gap is also becoming a less and less satisfactory solution, as the number of hours of maths given on other courses has been drastically reduced since the reforms known as the Bologna Process. With the challenge of improving and consolidating results in maths in the PISA educational assessment tests still unresolved, the most important component of the system is flagging: the teachers.

In Spain there has always been a lack of consensus in education, leading to unstable policies and debates which are all too often sterile (such as the recent issue of “parental consent”) (2). This new situation has thus taken us by surprise and found us unprepared to react. Where are we going to find all the teachers that we need? Are we willing to introduce major upgrades in wages and working conditions to entice people into education from other sectors? Can we competitively attract teachers and lecturers on a supply and demand basis? What long-term consequences will this shortage of maths teachers have? Will it affect maths education, or indeed our competitiveness at country level?

All these issues may well already be high priorities for the relevant public authorities, but that is not how it looks to the public. People have come to see politics as an arena for gladiatorial combat and a market for vested interests rather than a forum for reflection and expert administration with the best interests of the future at heart.

We professional mathematicians have no capability to help eradicate the problem outside our own field of action, i.e. our classes, our work as tutors, mentors, disseminators of knowledge and researchers, our books and papers. But what we can and must do is warn people of the danger of standing idly by and hoping that the issue will solve itself. Is it wise to wait until a change of cycle makes mathematics less attractive to the production sector again and people come back to teaching because they have no other outlet? Are we not at risk of becoming a smaller player in the international league of countries and nations if we do not have enough teachers and lecturers to educate our children in one of the most important subjects of the 21st century?

That being said, all we can do is carry on the dance, i.e. keep practising our profession with rigour and dedication wherever we are called on to do so. In my own case, this has brought me to the German region of Bavaria, which is making a major effort to reinforce its education system, its universities and its research specifically in the field of STEM. That effort is based on the conviction that much of the region’s future, including its industrial leadership and sustainability, are at stake.

But the Deusto Foundation and the Autonomous University of Madrid serve as a link, a kind of umbilical cord, through which I can keep abreast of what is happening (and, more worryingly, what is not happening) around here. From a Basque and European standpoint, our children deserve the best possible education. This is a matter that will soon be reflected even in our per capita income. A system that is incapable of filling teaching vacancies must do more than just put those vacancies out to tender. There is always the possibility of emigrating: many have seized it before and many others continue to do when they choose foreign schools in a desire to give their children the education that they deserve. But we specialists refuse to accept that this is the only solution. We will continue the dance here, to the sound of our own music, and will continue to warn of the danger of taking as good enough something that clearly is not.

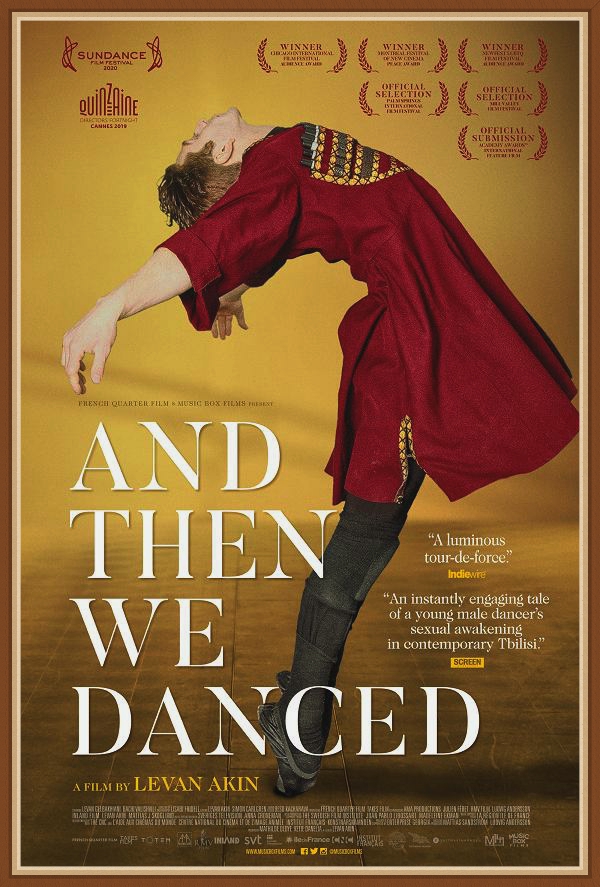

And Then We Danced is a film made in 2019 by Swedish director and writer Levan Arkin, who is of Georgian ancestry. It skilfully weaves the story of a traditional Georgian dance school in Tbilisi, where dance is the main symbol of national culture. The performing arts are taught there in an almost military fashion.

At the same time the film follows the ups and downs of a dance student who is highly talented but unorthodox in his way of expressing his art. Through dance and time spent with his instructors and fellow students he discovers his true nature, his homosexuality and sees that it is impossible for him to make a living and develop his career fully there without reproach, censure or even aggression. His brother, with whom he shared a bedroom from early childhood in their modest home, is both his close companion and his polar opposite as the very prototype of a strong, manly man. It is that brother who whispers to him “Get out of Georgia. There’s nothing for you here”. The film ends with him leaving the school and closing the door behind him after a unique, masterful dance performance of a contemporary, harmonious unorthodoxy that the keepers of tradition are unwilling to accept or approve. On closing that door he leaves behind everything – his roots, his family, his friends, his homeland – to embrace freedom. Hence the title of the film: And Then We Danced.

It is to be hoped that this talented dancer will one day be able to take his artistry back to Tbilisi. In the meantime, we need to set about making the changes that our education systems require.

[1] Translated to English by Chris Pellow (cgpellow@gmail.com) [2] Some regional governments mooted the idea of giving parents the right to vet the content of the subjects taught to their children.