If an alien were to visit us it would see that our civilisation has evolved to an admirable degree.

Just how it would rate the “state of the art” here would depend on how evolved its own civilisation was, because everything is relative, including progress.

Its perceptions would be conditioned by its ability to identify life and to communicate in our terms: we should not forget that our concept of life and intelligence is entirely conditioned by our own nature. The same would apply to us if we were to visit another world.

The well-known novel “La Planète des Singes” by French author Pierre Boulle (1912-2014) (filmed in 1968 as Planet of the Apes starring Charlton Heston and followed by several sequels) turns this situation on its head. Human journalist Ulysse Merou, a crewman on a voyage to the star Betelgeuse in the year 2500, lands on Soror, one of the planets orbiting the star. There, he finds that apes are in control and humans live in a state of savagery. Merou must show the apes that he is not an animal but an intelligent, rational being. He does so by sketching out Pythagoras’ theorem for ape Dr. Zira.

In this, Boulle links with the idea put forward by Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) that mathematics is the language of the universe.

An alien visitor to Earth would see things differently depending on just where it landed. Arriving in a rural village in Sub-Saharan Africa where there is hardly any running water or electricity would make a very different impression from landing atop a modern skyscraper in New York, Shanghai or Dubai.

Whenever we talk about globalisation, the welfare state, progress and civilisation, we are inadvertently taking as our frame of reference the average social state built up in our own minds from images, sensory perceptions and stereotypes, out of habit rather than on the basis of cross-checked quantitative data and critical thinking.

This is why reading, thinking, studying, conversing, debating and writing are useful: they help the brain to pick up on all those (often contradictory) details that it needs in order to hone its limited perception of reality and develop the essential ability to think critically.

We live in a heterogeneous world which we can often only visualise by oversimplifying it, for instance in the improbable context of a meeting with a visitor from another world.

But what kind of world does that creature actually encounter on landing? What kind of human beings does it meet? What is nature like in the area where it is located?

On imagining the scene we are highly likely to be conditioned not just by our own perceptions of our surroundings and our society but also by our studies and our reading of history or fantasy, or perhaps by remembered images from earlier experiences and, of course, from films.

The poem 37 Mugaz bestalde dudan lagun bakarrari (published in English as “37 Questions for my Only Contact on the Other Side of the Frontier”) by Basque writer Bernardo Atxaga is a clear example. It sets out some of the paradoxical questions that might be asked at such a meeting; questions which are meaningful in themselves but go unanswered: “On the other side of the frontier […] Do deep fish have any notion of the sun?”[1]

My own opinion is that deep fish have no notion of the sun but can sense light.

Steven Spielberg’s film ET (1982) provides another example. Things would have gone very differently if the script had started with the extraterrestrial arriving on our world and meeting not a sensitive, affectionate, curious, polite boy but some madman who hunted it down to show off its body as a trophy on social media (nowadays there is no need to waste time stuffing prey animals for display above the mantelpiece of your magnificent lounge).

As Basque writer and philosopher Joxe Azurmendi recently said at the presentation of his book Gizabere kooperatiboaz, “Inside every human being there still lives the ape that they once were”[2].

We do not all live in the same, single reality: our perceptions of it are coloured by our experience, by our critical mindset and by our capability for analysis. And all that is closely linked to the education that we have received.

Reverse analysis

Wherever our hypothetical alien lands and wherever it comes from, whatever the climate, the noise level and the pollution there, and whatever the company it keeps after its chance landing, it will surely undertake a process of reverse analysis in an attempt to understand not just the current state of our civilisation but how we got here, what foundations, what structure and what rules underlie the great web that we have so laboriously woven.

It would gradually begin a process of deconstruction to understand all the pieces in the construction set that makes up our current civilisation and its workings, our social organisation, the technology that we use, etc.

Little by little it would discover the architecture of our cities and our infrastructures and, in a regression analysis, would trace them back to how they looked a century earlier, in black and white, smaller, as yet with few cars; then further back to the cities of ancient Rome and Egypt; and then still further to mere groups of huts occupied by the first hominids to leave the caves.

Its analysis of the technological world that now surrounds us would soon reveal that it is based on information technology and robotics, which are the noble descendents of the Industrial Revolution and, ultimately, of mathematics.

By following any of these paths back through time our alien would gradually discover the leafy tree of science – physics, biology, chemistry, mathematics – and would eventually work its way to those ancient times when all knowledge grew out of a single root planted in the fertile soil of humanity’s insatiable thirst for knowledge; the outset of the great adventure of thought, based on ever more contradictory and imperfect models.

It would come to understand that our society rests largely on the social sciences and the humanities, which have provided the foundations for our economic, political and justice systems.

It would also see that morality, ethics, politics, law and religion all overlap in their attempts not just to give a structure to our society and establish limits, rules and rights, but also in their efforts to provide a rational explanation for the impossible: for the very existence of the universe and our role in it.

In that process of observation it would identify the great discipline of philosophy, from the Latin philosophĭa, which in turn came from the ancient Greek φιλοσοφία, which translates as “love of wisdom”, in the sense of the study of fundamental questions such as existence, knowledge, truth, morality, beauty, the mind and language.

This reverse process, this deconstruction or autopsy of our society would also reveal that from a historical perspective it came from nothing and gradually, over centuries, indeed millennia, rose to where we are today, still committing continual errors but committing fewer and fewer and doing better.

It would also observe a suspicious acceleration in our rate of progress, to the point where we risk sweeping away the very sustainability of our species on a planet on which we are inflicting more and more punishment.

It could not help but note that our level of process is by no means consistent, in terms not just of wealth, technology, health or what we colloquially refer to as “quality of life”, but also of social organisation, rights and freedoms.

It would not find it hard to make connections between the more visible levels of progress and the intellectual development of each culture, country or region.

And it would soon realise that one of they key points that characterises and distinguishes our society and determines the positions of countries and regions in the ranking of civilisations is their education systems.

Education

Having come this far, our alien would see that in Spain we are in a reasonably good position, albeit well behind the leading countries that guide the destiny of the world and shine the brightest in the field of new technologies or indeed at the Olympics.

It would also see that in the field of education opinions are widely divided and consensus is practically impossible, though the need for it may be recognised publicly. Numerous subsystems coexist even within systems where more cohesion, harmony and consistency might be expected. That is the case with us here.

It would probably be surprised to see that there is still an ongoing debate in our schools and our education system as to what role subjects such as Religious Studies, Ethics or Philosophy should play; and that they end up mixed together and pigeonholed as minor, optional subjects that students take only by choice.

This would strike our visitor as particularly paradoxical, because its careful deconstruction of society would have clearly shown that philosophy is one of the cornerstone disciplines of our civilisation, in that it is a synthesis of the noble efforts of human beings in a multitude of fields to make sense of the role of humanity in the universe and to structure our place in the world and, in short, our destiny.

Overall efforts to educate people in what we already know must necessarily involve philosophy, which is the traditional crossroads of all branches of knowledge.

Any subject can be taught in many different ways, for instance in chronological order or retrospectively, and Philosophy is no exception. The way in which it is taught may be open to debate, but the need to teach it should not be.

One major difficulty encountered by teachers is that we are frequently constrained by official syllabuses that drive us to present contents looking backwards from the present into the past as if through a rear-view mirror. This distorts the picture given of our sciences and of how they have matured, and makes them harder to understand and assimilate because no obvious visible motivation is shown. Indeed, it is more and more widely assumed that a historical perspective is essential to awaken interest among students and enhance their skills in understanding and analysis.

It is fine to argue about what content we should teach and in what order, but it is paradoxical for us still to have to defend the need for schools to reserve space for the sort of across-the-board, unifying thinking that philosophy has brought to our development and to the formation of a critical mindset in the citizens of tomorrow.

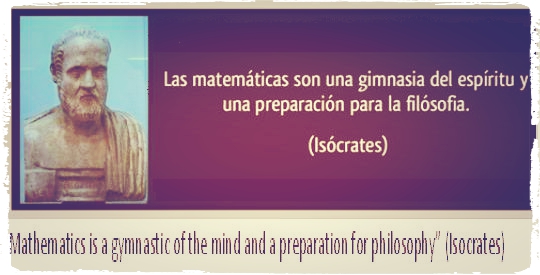

As a mathematician I must stress that philosophy and mathematics are sister disciplines that come together in logic, the theory of knowledge and, in general, in abstraction.

To train and develop knowledge it is necessary to accumulate data and structure information to enable each of us gradually to build up our own individual model of the world, so as to help us understand and transform it.

Our education system should be designed to offer the best possible launching pad for the ambitious project that is the life plan of each and every one of us.

To that end, the system now recognises mathematics, IT and statistics as essential in training us and educating us in deductive thinking, information processing, critical thinking and probability-based inference, but philosophy has been treated as the poor relation of the family.

Surrounded as we are today by electronic equipment and Wi-Fi, there is little room for critical thinking. However it is needed now more than ever.

Knowledge cannot be attained without a thirst for wisdom. On the path to that goal, which we must all take, it is essential to acquire perspective and be aware of what routes have already been explored in order to choose the best way forward.

Ultimately, human beings are destined to ask themselves the right questions (philosophy) by setting themselves the right problems (mathematics).

In ancient Greece little distinction was drawn between different branches of knowledge. Nowadays knowledge is compartmentalised, often artificially, so it is more necessary than ever to teach subjects such as Philosophy, which can offer a holistic overview of all that we have built so far. This is the only way to point our steps in the right direction in the future.

It is important to know that however much we oversimplify our model of the universe by making human beings – or God, or nature – our sole point of reference, if we are to obtain an up-to-date, transformational view we must integrate all these subsystems into a single, overall model. And that calls for a workshop, a specific laboratory, which philosophy can and must provide.

Being a Philosophy teacher is an exciting and at the same time extremely difficult job. Bringing together all the landmark events in the history of thought and unravelling the tangled web of knowledge is certainly an almost impossible task. But that is no reason to give up trying.

We need philosophy today more than ever, whether it is presented in chronological, historical or reverse order.

We now know that it is impossible to separate the concepts per se of philosophy and science in all their versions and interpretations. We therefore need to go back to the ancient sources, to the roots, when great thinkers recognised no boundaries between the different disciplines of knowledge.

But in that effort we are conditioned by a lack of consensus, and therefore run the risk that the regulatory belligerence of administrative authorities may end up marginalising the very subjects that humanise us in the fullest sense of the word.

It is certainly paradoxical that today’s great thinkers and scientists insist more and more that there is a need to unify disciplines so as to bring overall coherence to knowledge, while day-to-day events are pulling us in just the opposite direction.

Let us then go back to the roots to reconstruct our history and look to the future with perspective and clarity.

There is a verse in Basque by Joxean Artze that perfectly sums up this ongoing need: it translates as[1] “From the old source I drink, new water I drink, the water is always new, from the source of always”.

Acknbowledgements: Manuel de León (ICMAT-CSIC), Marta Macho (UPV-EHU), Carlos Martín-Vide (ERC), Javier San Martín (Activa Tu Neurona), Roberto Rodríguez del Río (UCM), Soledad Rodríguez Salazar (UCM).

En defensa de la Filosofía [“In Defence of Philosophy”], Artium, Gasteiz, 16 September 2016

Agora Filosofia Elkartea

Enrique Zuazua

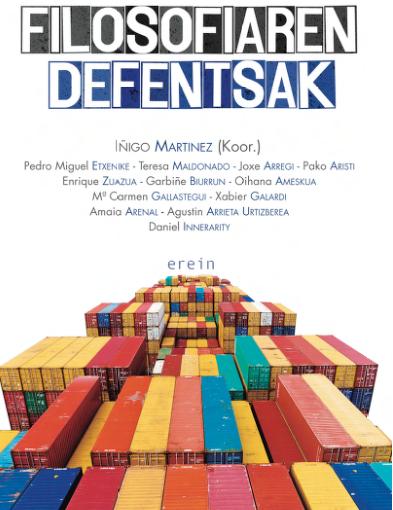

The publishing house EREIN has published a book that brings together all the presentations from the seminar In Defence of Philosophy, held on 16 September 2016.

The book comprises a variety of short texts defending philosophy, arguing for the value of thought in the human condition and against the cutbacks that the planned new curriculum makes in History and Philosophy, which is to be relegated from a core to an optional subject and maintained only in one upper-secondary itinerary.

The texts are by qualified representatives of different branches of knowledge. The first chapter can be downloaded in Spanish here.

The report on the presentations at the seminar which appeared in the daily newspaper GARA can be read in Basque here.

The Basque newspapers El Diario Vasco, Berria and Noticias de Guipuzkoa also published articles on the seminar which can be downloaded via

the links provided here.

[1] “Mugaz bestaldean… Arrain abisalek ba ahal dute aurresentipenik eguzkiaz…?”

[2] “Izan gine tximinoak bizirik dirau gure barruan”

[3] “Iturri zaharretik edaten dut, ur berria edaten, beti berri den ura, betiko iturri zaharretik”