PDF version | Download Matlab Code…

In [3], we develop a WKB analysis for the propagation of the solutions to the following one-dimensional nonlocal Schrödinger equation

\begin{align}\label{main_eq}

\mathcal{P}_s u:= \left[i\partial_t + \ffl{s}{}\right]u = 0, &\;\; (x,t)\in\RR\times(0,+\infty),

\end{align}

with highly oscillatory initial datum

\begin{align}\label{in_dat}

u(x,0) = u_{\textrm{\small in}}(x) e^{i\frac{\xi_0}{\varepsilon} x}:=u_0(x),\;\;\; \xi_0\in\RR.

\end{align}

In (\ref{main_eq}), $\ffl{s}{}$ is the fractional Laplacian, defined for all $s\in(0,1)$ and for any function $f$ sufficiently smooth as the following singular integral

\begin{align*}

\ffl{s}{f}(x):=\ccs\; P.V. \int_{\RR}\frac{f(x)-f(y)}{\kernel{1+2s}}\,dy,

\end{align*}

with $\ccs$ a normalization constant given by

\begin{align*}%\label{ccs}

\ccs:= \left(\int_{\RR} \frac{1-\cos(z)}{|z|^{1+2s}}\,dz\right)^{-1} = \frac{s2^{2s}\Gamma\left(s+\frac 12\right)}{\sqrt{\pi}\Gamma(1-s)},

\end{align*}

where $\Gamma$ is the usual Gamma function. The parameter $\varepsilon$ in (\ref{main_eq}) and in (\ref{in_dat}) represents the fast space and time scale introduced in the equation, as well as the typical wavelength of oscillations of the initial data. Moreover, we will assume the initial phase $u_{\textrm{\small in}}$ to be an $L^2(\RR)$ function, so that we have $u_0\in L^2(\RR)$.

Our study is motivated by control problems. Indeed, the well-known boundary controllability and identifiability properties of solutions of wave-like equations hold because of the fact that the energy of solutions is driven by characteristics that reach the boundary where the controllers or observers are placed. This, in particular, allows the so-called observability of the solutions (namely, the possibility to obtain estimates of the total energy in terms of the energy concentrated on the support of the control along time), which is by now known to be equivalent to control properties. In the framework of wave-like processes, observability is possible if and only if the geometric control condition (GCC), requiring all rays of geometric optics to enter the control region during the control time, holds ([1]).

In the particular case under analysis, the construction that we obtain is then applied to the study of controllability properties for the one dimensional fractional Schrödinger equation

\begin{align}\label{schr_control}

\begin{cases}

iu_t+\ffl{s}{u} = g\chi_{\omega\times(0,T)}, & (x,t)\in (-1,1)\times(0,T)

\\

u\equiv 0, & (x,t)\in(-1,1)^c\times(0,T)

\\

u(x,0)=u_0(x), & x\in(-1,1),

\end{cases}

\end{align}

where $\omega$ is a neighborhood of the boundary of the space domain $(-1,1)$. In particular, it is possible to find confirmation to the following facts, proved in [2]:

- For $s> 1/2$, null controllability holds in any finite time $T>0$. In other words, given any $u_0\in L^2(-1,1)$ there exists a control function $g\in L^2(\omega\times(0,T))$ such that the solution to (\ref{schr_control}) satisfies $u(x,T)=0$.

- For $s=1/2$, the same result holds if we assume the controllability time $T$ to be large enough, i.e $T\geq T_0>0$.

- For $s<1/2$, the equation (\ref{schr_control}) is not null controllable.

The above facts are related to the well-known property that the solutions to wave-like equations propagate along the so-called rays of geometric optics. These rays are nothing more than the projection to the physical time-space of the null bicharacteristic, solutions to the Hamiltonian system associated to the equation.

In our case, since $\mathcal{P}_s=i\partial_t+\ffl{s}{}$ is a pseudo-differential operator with symbol $p_s(x,t,\xi,\tau) = \tau – |\xi|^{2s}$, the Hamiltonian system is given by

\begin{align}\label{char_syst}

\begin{cases}

\dot{x}(\sigma) = \partial_\xi p_s = \pm 2s|\xi(\sigma)|^{2s-1}, & x(0)=x_0

\\

\dot{t}(\sigma) = \partial_\tau p_s = 1, & t(0)=t_0

\\

\dot{\xi}(\sigma) = -\partial_x p_s = 0, & \xi(0)=\xi_0

\\

\dot{\tau}(\sigma) = -\partial_t p_s =0, & \tau(0)=|\xi_0|^{2s}.

\end{cases}

\end{align}

Moreover, without losing generality we may assume $t_0=0$. Then, (\ref{char_syst}) can be solved explicitly, and we obtain the following expressions for the bicharacteristics

\begin{align*}

\begin{cases}

x(\sigma) = x_0 \pm 2s|\xi_0|^{2s-1}\sigma

\\

t(\sigma) = \sigma

\\

\xi(\sigma) = \xi_0

\\

\tau(\sigma) = |\xi_0|^{2s}.

\end{cases}

\end{align*}

In particular, the rays of $\mathcal{P}_s$ are given by the curves $(t,x_0\pm 2s|\xi_0|^{2s-1}t)\in(0,+\infty)\times\RR$. Notice that, as one expects since the operator has constant coefficients, these rays are straight lines.

The approach that we use for building localized solutions is quite standard. In particular, we look for quasi-solutions to (\ref{main_eq}) introducing the ansatz

\begin{align}\label{ansatz}

\ue{u}(x,t) = \varepsilon^s e^{i\left[\xi_0\varepsilon^{-1}x\,+\,|\xi_0|^{2s}\varepsilon^{-2s}t\right]}\sum_{j\geq 0}\varepsilon^{\frac{s}{2}j}a_j\left(x,\varepsilon^{\frac{3}{2}s}t\right),

\end{align}

where the normalization constant $\varepsilon^s$ is chosen asking that the function $\ue{u}$ has $H^s(\RR)$-norm of the order $\mathcal O(1)$. The identification of the $a_j$-s is then carried out imposing

\begin{align*}

\mathcal{P}_s\ue{u} = O(\varepsilon^{\infty}),

\end{align*}

thus obtaining a series of PDEs in which it is possible to clearly separate the leading order terms, with respect to $\varepsilon$, from several remainders which will vanish as $\varepsilon\to 0$. This generates a cascade system for the functions $a_j$, which can then be determined as the solution of certain given Partial Differential Equations. In our case, the cascade system is the following one

\begin{align}\label{cascade_system}

\begin{cases}

i\partial_\tau a_0 + \mathcal{C}_{\frac s2} \mathcal{D}^{\frac{s}{2}} a_0 = 0

\\

i\partial_\tau a_1 + \mathcal{C}_{\frac s2} \mathcal{D}^{\frac{s}{2}} a_1 + \mathcal{C}_{s} \mathcal{D}^{s} a_0 = 0

\\

i\partial_\tau a_2 + \mathcal{C}_{\frac s2} \mathcal{D}^{\frac{s}{2}} a_2 + \mathcal{C}_{s} \mathcal{D}^{s} a_1 + \mathcal{C}_{\frac{3s}{2}} \mathcal{D}^{\frac{3s}{2}} a_0(\theta,\tau) = 0, & \displaystyle x\leq\theta\leq x+\frac{\varepsilon}{\xi_0}q

\\

i\partial_\tau a_j + \mathcal{C}_{\frac s2}\mathcal{D}^{\frac{s}{2}}a_j + \mathcal{C}_{s} \mathcal{D}^{s}a_{j-1} + \mathcal{C}_{\frac{3s}{2}} \mathcal{D}^{\frac{3s}{2}}a_{j-2}(\theta,\tau) + \ffl{s}{a_{j-3}}, & j\geq 3

\\

&\displaystyle x\leq\theta\leq x+\frac{\varepsilon}{\xi_0}q.

\end{cases}

\end{align}

with $\tau:=\varepsilon^{\frac 32 s}t$ and where $\mathcal{D}^{\,\beta}$ denotes the following fractional derivative of order $\beta$

\begin{align*}

\mathcal{D}^{\beta} f(x):= \frac{1}{\Gamma(1-\beta)}\int_{-\infty}^x \frac{f'(y)}{(x-y)^{\beta}}\,dy.

\end{align*}

Moreover, (\ref{cascade_system}) is uniquely solvable with initial conditions imposed at $\tau = 0$ and this, of course, allows to identify the expressions of the functions $a_j$. See [3] for more details.

Now, it is possible to show that the quasi-solutions that can be computed by using the ansatz (\ref{ansatz}) are in fact localized along rays. In more detail, we have the following result

Theorem 1. Let $u_{\textrm{\small in}}\in L^2(\RR)$ and let $\ue{u}$ be constructed employing the expansion (\ref{ansatz}). Then, for any $\varepsilon>0$ we have:

- The functions $\ue{u}$ are approximate solutions to (\ref{main_eq}):

\begin{align*}

\norm{u_0(x)-\ue{u}(x,0)}{L^2(\RR)} = \mathcal{O}(\varepsilon^{\frac{1}{2}}),

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

\norm{u(x,t)-\ue{u}(x,t)}{L^2(\RR)} = \mathcal{O}(\varepsilon^{\frac 12}).

\end{align*} - The initial energy of $\ue{u}$ remains bounded as $\varepsilon\to 0$, i.e.

\begin{align*}

\norm{\ue{u}(x,0)}{H^s(\RR)}^2 \approx 1.

\end{align*} - The energy of $\ue{u}$ is exponentially small off the ray $(t,x(t))$:

\begin{align*}

\int_{|x-x(t)|>\varepsilon^{\frac 14}} \left|\ffl{\frac s2}{\ue{u}}(x,t)\right|^2\,dx = \mathcal O(\varepsilon^{\frac 14}).

\end{align*}

Since the quasi-solution $\ue{u}$ to our original system are concentrated along the rays, they propagate with the group velocity of the plane wave solutions, which can be computed as follows. First of all, rewrite

\begin{align*}

e^{i\left[\xi_0\varepsilon^{-1}x\,+\,|\xi_0|^{2s}\varepsilon^{-2s}t\,\right]} = e^{it\left[\xi_0\varepsilon^{-1}\left(\frac xt\right) + \,|\xi_0|^{2s}\varepsilon^{-2s}\,\right]} = e^{it\phi(x,t,\xi_0,\varepsilon)}.

\end{align*}

Hence, $v:=|x/t|$ is obtained solving the equation

\begin{align*}

\frac{\partial\phi}{\partial \xi_0} = \varepsilon^{-1}\frac xt + 2s\varepsilon^{-2s}|\xi_0|^{2s-1}\textrm{sgn}(\xi_0) = 0,

\end{align*}

from which we immediately find that

\begin{align*}

v=\left|\frac xt\right| = 2s\varepsilon^{1-2s}|\xi_0|^{2s-1}.

\end{align*}

Moreover, this group velocity can be analyzed in terms of $s$ and of the frequency $\xi_0$. Firstly, we immediately see that for $s=1/2$ we have

\begin{align*}

v=1,

\end{align*}

i.e. the velocity is constant and independent of the frequency $\xi_0$. For $s\in(0,1/2)$, instead, we have that $1-2s>0$. Hence, taking $\varepsilon<1$, we easily get

\begin{align*}

v<|\xi_0|^{2s-1}.

\end{align*}

Finally, for $s\in(1/2,1)$ the situation is the opposite. We have $1-2s<0$ and, for $\varepsilon<1$,

\begin{align*}

v>|\xi_0|^{2s-1}.

\end{align*}

In view of these behaviors, we can conclude that:

- For $s> 1/2$, the group velocity increases with the frequency.

- For $s=1/2$, the group velocity remains constant.

- For $s<1/2$, the group velocity decreases with the frequency.

Therefore, the high-frequency solutions are travelling faster and faster, for $s>1/2$, and slower and slower, for $s<1/2$. This behavior has then consequences from the point of view of observation properties for the solutions. In more detail,

- For $s>1/2$, the velocity of propagation of the rays allow them to be observable in any finite time $T>0$.

- For $s=1/2$, the velocity of propagation being constant, a minimum observation time $T_0$ is needed.

- for $s<1/2$ the high frequency rays may not reach the control region, thus implying the failing of controllability properties.

This, in particular, confirms the already known results presented in [2].

In what follows, we present some simulations which show the propagation of solutions to the fractional Schrödinger equation (\ref{main_eq}) corresponding to initial data in the form (\ref{in_dat}).

For the numerical resolution of the equation, we employed a uniform mesh in the space variable and a FE discretization of the fractional Laplacian, obtained following the methodology presented in [4]. Moreover, we used a Crank-Nicholson scheme in time, which is known to be stable for the Schrödinger equation. The initial data $u_0$ has been chosen as

\begin{align*}

u_0(x) = e^{-\frac \gamma2 (x-x_0)^2}e^{i\frac {\xi_0}{\varepsilon} x},

\end{align*}

where the profile $u_{\textrm{in}}(x)$ is given by a Gaussian with standard deviation measured in terms of the parameter $\gamma$, which is related to the mesh size $h$. In particular we chose $\gamma = h^{0.9}$. Finally, for the oscillations we considered frequencies $\xi_0=\pi^2/16$ and $\xi_0=2\pi^2$.

In Video 1, we show the plots for $\xi_0=2\pi^2$ and different values of $s\in(0,1)$. The space domain has been chosen to be the interval $(-1,1)$, while we considered a time interval of $5$ seconds.

Video 1. Propagation of the solution for $\xi_0 = 2\pi^2$ and different values of $s$.

It is seen there that, for small values of $s$, say $s=0.1$, the solution remains concentrated along rays which propagate only in the vertical direction. In other words, there is no propagation in space and, as we mentioned before, this implies that it will not be possible to control these solutions, no matter how one places the controls. For $s=0.5$, instead, the plots show that the solutions propagate along rays which reach the boundary of the space domain in finite time and are reflected according to the laws of optics. This translate in the fact that, provided that the time is large enough, it will be possible to control these solutions, acting with a control distributed in a neighbourhood $\omega$ of the boundary. The case of high values of the power $s$ of the fractional Laplacian is the most puzzling one. For instance, for $s=0.9$ our plots seem to show a lost of concentration of the solution along the ray, while our theoretical results would suggest that this concentration is preserved. On the other hand, we believe that what the simulations are showing is not in contradiction with the theory. In our opinion, it is only a numerical effect, which has two possible interpretations.

First of all, for $s>1/2$, the velocity of propagation of the solutions is increasing. As a consequence, in the time framework that we are considering the waves reach the boundary and are reflected many more times than in the case $s=1/2$. This large number of reflections is quite hard to clearly distinguish a the discrete level, even when working with very fine meshes (for our simulations, for instance, we are considering a mesh of $500$ points, corresponding to a step $h$ of the order of $10^{-3}$).

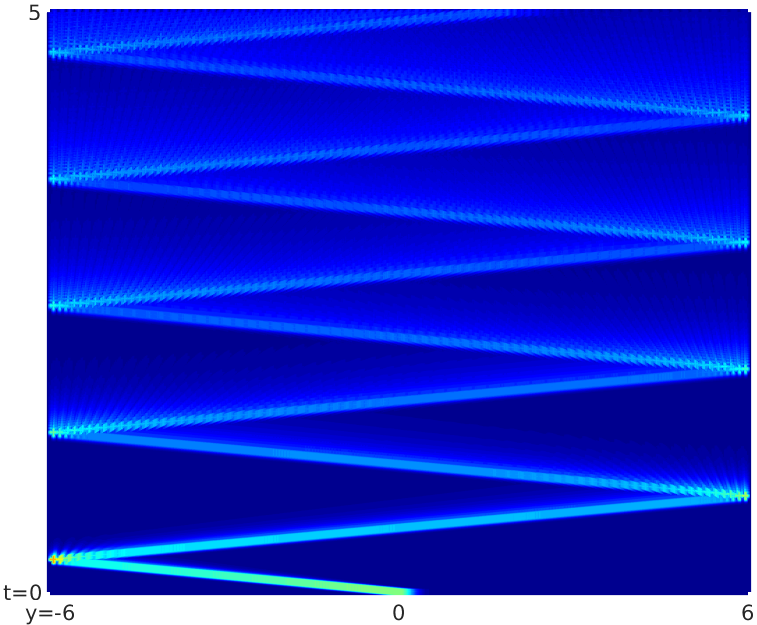

A second possible interpretation is that this strange phenomenon appearing in the plot can be explained with the accumulation of higher order terms in the asymptotic expansion of $\ue{z}$ which, combined with the small size of the space interval considered, enhance a chaotic behavior. This interpretation is supported by the fact that, as it is shown in Video 3, enlarging the space domain up to $(-6,6)$ it is possible to appreciate again the localization of the solution along the rays.

In Video 2, the simulations have been run with an initial datum with frequency $\xi_0=\pi^2/16$. The plots obtained show a behavior which is totally analogous with what observed in Video 1:

- For $s=0.1$, the solutions are once again concentrated along vertical rays, without propagation in time and, therefore, without possibility of being controlled.

- For $s=0.5$, we have propagation with constant velocity, and the ray reaches the boundary in finite time.

- For $s=0.9$ the chaotic comportment is still present.

Video 2. Propagation of the solution for $\xi_0 = \pi^2/16$ and different values of $s$.

Once again, the most surprising case is the last one, for $s>0.5$, in which the simulations seem to display dispersive features. Nevertheless, as we mentioned before, we retain that this does not contradict the theoretical results, and we think that this chaotic behavior is purely a numerical effect generated by the small size of the space interval $(-1,1)$, by the high velocity of propagation of the solutions, and by the accumulation of high order terms in the asymptotic expansion. In fact, we can observe that the enlargement of the space domain up to $(-6,6)$ seems to fix the problem, and the localization of the solution along the rays appears once again (see Video 3). This, in our opinion, justifies our interpretation of the phenomenon.

Video 3. Propagation of the solution for $s=0.9$ on the space interval $(-6,6)$.

Bibliography

[1] Bardos, C., Lebeau, G., and Rauch, J. Sharp sufficient conditions for the observation, control, and stabilization of waves from the boundary. SIAM J. Control Optim. 30, 5 (1992), 1024–1065.

[2] Biccari, U. Internal control for non-local Schrödinger and wave equations involving the fractional Laplace operator. ESAIM: COCV: to appear. (2018).

[3] Biccari, U., and Aceves, A. B. WKB expansion for a fractional Schröodinger equation with applications to controllability. Submitted. (2018).

[4] Biccari,U., and Hernández-Santamaría, V. Controllability of a one-dimensional fractional heat equation: theoretical and numerical aspects. HAL Preprint – hal-01562358. (2017).