Solving the driving problem with a repulsion force

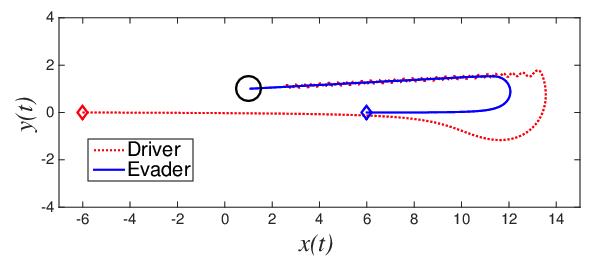

The standard approach for solving a driving problem is a leadership strategy, based on the attraction that a driver agent exerts on other agents, [1],[2],[3]. Repulsion forces are mostly used for collision avoidance, defending a target or describing the need for personal space [3], [4]. We present a “guidance by repulsion” model [5] describing the behaviour of two agents, a driver and an evader. The driver follows the guided but cannot be arbitrarily close to it, while the evader tries to move away from the driver beyond a short distance. The key ingredient of the model is that the driver can display a circumvention motion around the evader, in such a way that the trajectory of the evader is modified due to the repulsion that the driver exerts on the evader. We propose different open loop strategies for driving the evader from any given point to another assuming that both switching the control and keeping the circumvention mode active have a cost. However, numerical simulations show that the system is highly sensitive to small variations in the activation of the circumvention motion, so a general open-loop control would not be of practical interest. We then propose a feedback control law that avoids an excessive use of the circumvention mode, finding numerically that the feedback law significantly reduces the cost obtained with the open-loop control.

The “Guidance by Repulsion” model

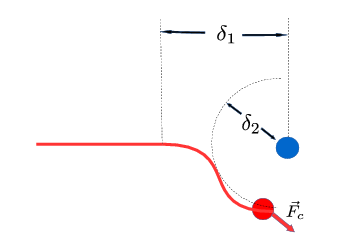

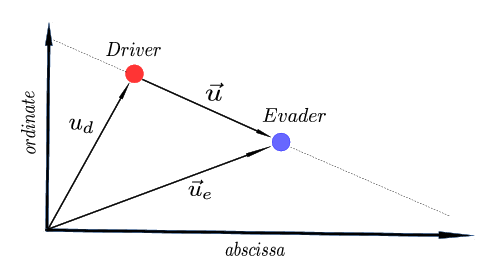

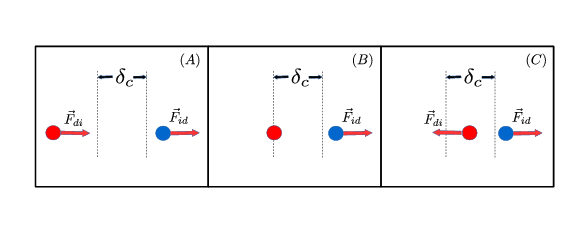

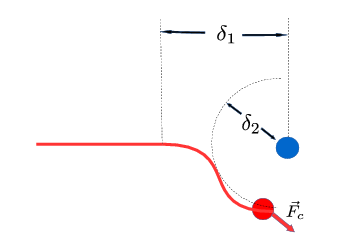

\begin{equation} \dot{\vec{u}}_d(t) & = \vec{v}_d(t), \end{equation} \begin{equation} \dot{\vec{u}}_e(t) & = \vec{v}_e(t), \end{equation} \begin{equation} \dot{\vec{v}}_d(t) & = {1 \over m_d} \left[ - C^E_D {\vec{u}(t) \over \|\vec{u}(t)\|^2} \left( 1 - {\delta_c^2 \over \|\vec{u}(t)\|^2} \right) - \nu_d \vec{v}_d(t) \right. \nonumber \\ & \left. - C_{\rm R} {\delta_1^4 \over \|\vec{u}(t)\|^4} \left( \vec{u}_d(t) - \vec{u}_e(t) - \kappa(t) \delta_2 \, {\vec{u}^\bot \over \| \vec{u}(t) \|} \right) \right], \end{equation} \begin{equation} \dot{\vec{v}}_e(t) & = {1 \over m_e} \left[ C^D_E { \vec{u}(t) \over \|\vec{u}(t)\|^2} - \nu_e \vec{v}_e(t) \right], \end{equation} \begin{equation} \vec{u}_d(t_0) & = \vec{u}_d^0, \quad \vec{u}_e(t_0) = \vec{u}_e^0, \vec{v}_d(t_0) = 0 \quad \mbox{and} \quad \vec{v}_e(t_0) = 0. \end{equation} where $\vec{u}_d, \vec{v}_d \in \mathbb{R}^2$ are driver’s position vector and velocity vector respectively. $\vec{u}_e, \vec{v}_e \in \mathbb{R}^2$ are evader’s position vector and velocity vector respectively (Figure 1).

The control variable is $\kappa(t) \in \{-1, 0,1 \}$. $\delta_1, \delta_2, \delta_c$ are distances. $C_R, C_D^E, C_E^D$ are coefficients of the atraction-repulsion force and circumvection force. $m_e, m_d$ are the masses of the evader and the driver. $\nu_e, \nu_d$ are the frictions of the evader and the driver (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

The optimal control problem and the feedback law

Let denote by $B_\rho(T)$ a ball of radius $\rho$ centered in the target $T$, $N_{\rm ig}(\kappa)$ is the number of times that $\kappa(t)$ changes from 0 to $\pm 1$ and ${\cal C}(\kappa) = \int_{t_0}^{t_f} | \kappa(t) | dt$.

We define the cost functional:

\begin{align}

J(\kappa) \stackrel{def}{=} \sigma_1 N_{\rm ig}(\kappa) + \sigma_2 \, {\cal C}(\kappa),

\end{align}

and we formulate the optimal control problem:

\begin{align}

(OCP) \; \left\{

\begin{array}{ll}

{\rm Min} \, J(\kappa) = &\sigma_1 N_{\rm ig}(\kappa) + \sigma_2 \, {\cal C}(\kappa) \\

\kappa \in U_{\rm ad} = & \big\{ \kappa : [t_0,t_f] \to \{-1,0,1\} \\ & \mbox{ such that }

\vec{u}_e(t_f) \in B_\rho(T) \big\}

\end{array}

\right.

\end{align}

For systems that are subject to conditions of high sensitivity, closed-loop or feedback controls offer the possibility of correcting the state of the system for deviations from the desired behaviour instantaneously.

The feedback control law is based on: 1- the alignment of the driver and the evader with the target point $T$ is easier to observe the orientation of the vector $\vec{v}_e(t)$ 2- when the driver is sufficiently far from the evader, $\kappa(t)$ can be set to zero.

We define the alignment of the agents and the characteristic function:

\begin{align}

a(t) &= (\vec{u}_T - \vec{u}_d) \cdot (\vec{u}_e - \vec{u}_d)^\bot% \\

%&= (u_T^x - u_d^x)(u_d^y - u_e^y) + (u_T^y -u_d^y)(u_e^x-u_d^x). %\quad

\end{align}

\begin{eqnarray}

{\cal X}(t) = \left\{

\begin{array}{cl}

0 & \mbox{ if } r^3(t) \gg \delta_2, \\

1 & \mbox{ if not},

\end{array}

\right.

\end{eqnarray}

The feedback control law can then be written as follows:

\begin{eqnarray}

\kappa_{\rm F}(t) = {\cal X}(t) \times \left\{

\begin{array}{cl}

0 & \mbox{ if } |a(t)| \le \bar{a} \\

%\mbox{ and }(\vec{u}_e - \vec{u}_T) \cdot (\vec{u}_e - \vec{u}_d) < 0,% \\ {\rm sign}\{a(t)\} & \mbox{ if } |a(t)| > \bar{a}

%\; \mbox{ or }\; \, (\vec{u}_e - \vec{u}_T) \cdot (\vec{u}_e - \vec{u}_d) \ge 0 .

\end{array}

\right.

\label{fidbaclaw}

\end{eqnarray}

Perspectives

- Formulate the problem for N evader and study the evolution of the cost depending on the number on evaders

- The sheepherding problem is an example of the use of repulsion forces for guiding a flock. One of the close future work is building a sheepherding model, including stochastic terms in it, using experimental data.

- Prove the controllability of the problem.

- Study the sensibility and the efficiency of the model depending on the parameters of the model, in special on the critical distances.

- Mean–field theorem for the guidance by repulsion model passing to the limit in the number of evaders, $N \rightarrow \infty$, as in [6].

- Study of the problem for N evaders and M drivers.

- Formulate the problem in $\mathbb{R}^3$.

References

[1] Alfio Borzì and Suttida Wongkaew. Modeling and control through leadership of a refined flocking system. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences,25(02):255–282, 2015.

[2] Marco Caponigro, Massimo Fornasier, Benedetto Piccoli, and Emmanuel Trélat. Sparse stabilization and control of alignment models. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences, 25(03):521–564, 2015.

[3] Francesco Ginelli, Fernando Peruani, Marie-Helène Pillot, Hugues Chaté, Guy Theraulaz, and Richard Bon. Intermittent collective dynamics emerge from conflicting imperatives in sheep herds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(41):12729–12734, 2015.

[4] R Escobedo, C Muro, L Spector, and RP Coppinger. Group size, individual role differentiation and effectiveness of cooperation in a homogeneous group of hunters. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 11(95):20140204, 2014.

[5] Ramón Escobedo, Aitziber Ibañez, and Enrique Zuazua. Optimal strategies for driving a mobile agent in a guidance by repulsion model. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 39:58–72, 2016.

[6] José Antonio Carrillo, Young-Pil Choi, and Maxime Hauray. The derivation of swarming models: mean-field limit and wasserstein distances. In Collective dynamics from bacteria to crowds, pages 1–46.Springer, 2014.